Billy Miller -The Conclusion

DM Testa

On a blustery cold day shortly after their trials, Charles Makley, James Lanning and Dick Heath traveled two hundred and fifty miles west to the Idaho State Penitentiary near Boise, Idaho. It was a long, dreary trip that would have been unremarkable but for one thing. The person who came to retrieve the trio and take them back to the pen was the warden, himself.

An Indeterminate Sentence

Thirty three years old at the time when he personally escorted Makley and company to Boise, Idaho, John Wilson Snook was far from being the typical prison warden.

The job of warden was a political appointment, a reward for being affiliated with the right party. At the Idaho State Penitentiary, most filled the post for a little over two years. However, Snook proved an exception to the rule. Appointed in March of 1909, he ran the Idaho State Penitentiary his way for seven years before being forced to step down.

And his way was proactive. Little time was spent sitting behind a desk shuffling papers (which accounted for his messy roll top desk). Born and raised on the Idaho frontier, Snook spent his early twenties as the deputy United States marshal in Alaska during the gold rush of the 1890s. Returning after seven years, he bought a ranch in Northeast Idaho and became an active member in the Republican Party before taking on the job of warden.

From the start, Snook used his experience dealing with adventurers and outlaws of the Yukon to manage the penitentiary. Nothing the convicts or guards came up with seemed to throw him.

One afternoon, as a line of prisoners were being marched back to their cells, six broke rank, making a mad dash for the warden’s office. They may have been hoping to catch him by surprise and take a hostage but Snook heard the commotion. As the leaders threw open the door, he calmly stood up from his chair with a pair of revolvers pointed at the prisoners. Shocked, the convicts threw up their hands in surrender.

When prisoners escaped, Warden Snook often led the search, using a bloodhound named “Red” to successfully track down the convicts. And when the law required a convict to be executed, Snook performed the hangings instead of passing it off to someone else.

Leading by example was how Warden Snook operated. And this applied to the prisoners as well. Snook preferred that the inmates housed in the Idaho State Penitentiary be given indeterminate sentences. They should come in with at least a minimum sentence but their actions would determine how long they actually stayed. Or in other words, good behavior would be rewarded by a shorter sentence. Snook felt that he was in a better position than a judge to determine when a convict should be released.

Intent on keeping troublemakers separated from the general population, Snook often handled the transfer of prisoners to the penitentiary himself. It gave him the opportunity to take a so-called “measure of the man”. Although he was outnumbered, bringing three boys back to Boise presented no challenge to the self-sufficient warden. And so Charley Makley began to learn what it would take to get along in a prison run by a no-nonsense warden.

A Congregate System

When the group arrived in Boise, they were taken by a horse-drawn paddy wagon to the penitentiary which was about three quarters of a mile away from the city limits at that time. As Makley, Lanning and Heath turned into the prison gates and headed up the long drive, they got an eyeful of how the Old West handled security.

The prison itself was built like an ominous fortress. Stone turrets and walls gave the appearance of being able to withstand a siege longer than the Trojan War. The big difference was it was built to hold people in rather than keep them out.

The pen had started construction in 1870 on an elevated area that had been called “Table Rock” by the Shoshoni Indians. The location was a rich source for convict-quarried sandstone. Inmates who had been sentenced to hard labor dug the rock from the prison quarry which was located on the ridge above the penitentiary. Not only was the sandstone used for new buildings at the prison but it was hauled into Boise for the Idaho State Capital building. As Warden Snook saw it, this type of hard labor was an opportunity for the prisoners to build moral character.

However that particular shoe hadn’t dropped yet for Charley Makley. Because it was the dead of winter, the stone quarry had been closed down the month before. Instead the convicts were busy harvesting ice. The men damned up a part of the nearby river, allowing enough water to freeze into ice. This ice (roughly three hundred tons) would take the penitentiary through the upcoming summer months. The job consisted of cutting up the ice into blocks, loading it onto horse-drawn sleds and then dragging the loads back to the penitentiary to be stacked into the prison ice house.

Warden Snook was not alone in believing that the more inmates had to do to fill their time, the less problems they would have during confinement. This “congregate system” was being adopted throughout most federal prisons. The concept was simple. Prisoners were confined to sleeping cells at night but allowed to work together during the day. Silence was encouraged, but not total isolation from human contact.

Each sleeping cell measured six feet by eight feet with the only windows located on walls opposite the cell blocks. At that time, there was no individual plumbing. The inmates used “honey buckets” that were stored in the ventilation shaft of each cell. Convicts were let out each morning to empty the contents.

Originally the cell house was supposed to be a part of a much larger building which was to be completed by inmate labor. A lack of funding caused the construction to stop. By the time Makley, Lanning and Heath arrived, overcrowding was a severe problem. Each cell which had been meant for one, now housed two prisoners.

In contrast to the cells, the dining hall offered the inmates more room to “congregate” with their fellow man in a larger, better ventilated area. It housed the prisoners’ dining room, the guards’ dining room and kitchen. A typical meal was made up of food the inmates grew at the prison farm. Although the prisoners did have more space, they were required to eat their meals in silence while armed guards watched from a balcony above called the “Birds Nest”.

In 1910, when Charley Makley was incarcerated at the penitentiary, there was a communal plunge bath housed in the lower level of the dining hall that was used by the prisoners for their “Saturday night baths”.

During the early part of the nineteenth century, community swimming pools (usually built indoors on a grand scale) were known as “plunge baths” The plunge bath at Idaho State Penitentiary may have been communal but that was about all it had in common with the ones open to the general public. The stone block and stucco wading pool-like tub was used for hygiene not recreation. Twenty or so prisoners at a time got in to the tepid to icy-cold water to scrub off the filth and sweat accumulated during the week. The inmates used this bath until 1926 when the state declared it unsanitary and installed showers.

The Bull Gang

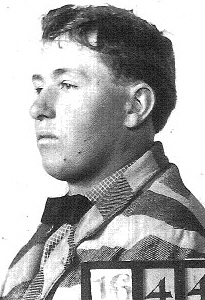

Although the three boys may have been intimidated by the time they arrived at the penitentiary, what happened next had to have been a shock. Immediately upon admittance, each was photographed facing the camera then the trio had to shuck off their clothes to be examined in detail. Any freckle, scar, mole or other unique characteristic was noted in a chart. Although the Bertillon system had not yet been officially adopted by the Idaho State Penitentiary, not much escaped the sharp eyes of Warden Snook.

Charley Makley was already missing the tip of his left index finger. It was noted that he had “mashed” it off. His left testicle hung lower than the right due to a “rupture”. However, the accident that caused his right leg to be shorter than the left hadn’t yet happened. He stood straight at five feet six and a half inches and weighed in at one hundred and forty-eight pounds. Shoe and hat sizes were also recorded for posterity. Charley wore a 7 and 6- 7/8 respectively.

After each boy had been gone over with a fine tooth comb (quite literally since lice was often a fixture in jails), they were issued their striped prison uniforms. Another photograph was taken, this time in profile then they were marched off to their cells.

In 1910, the Idaho State Penitentiary received ninety five men. All of them started out wearing the “zebra gear” of wide black and white penitentiary stripes upon arrival. After three months of good behavior, an inmate could graduate to a suit of narrower stripes which was known as a second grade uniform. In six months, the privilege of wearing the cadet gray suit was available to any convict who had behaved himself. Warden Snook believed this gave the men a chance to earn a measure of self-respect instead of compelling them to wear a badge of penitentiary disgrace.

In keeping with the “hard labor” part of their sentencing, Makley, Lanning, and Heath were put to work immediately, being assigned job details inside and outside the prison walls. The penitentiary baseball team names were an apt enough description of how those assignments were made. The Hillmen were those trusted enough to work in the quarry outside the prison walls while the Yardmen were confined to the compound.

James Lanning and Dick Heath would have been on the Hillmen team, since they were put to work as laborers in the stone quarry. However Charley’s status is a mystery. On the May 3rd, 1910 census, he is also listed as a laborer but where he worked remains unknown since the entry is illegible. It appears that he wasn’t with Lanning or Heath at the time.

Those prisoners who worked at various miscellaneous jobs such as hauling stone, weeding, or other manual labor were known by an all encompassing title of “The Bull Gang”. It’s likely that Charley was a member of this group since it would have been easier to keep an eye on him.

The pittance each inmate earned while working was often spent at the prison commissary. Extra food, tobacco, and other supplies could be purchased with special penitentiary money. Besides eating, sleeping and work, most of the convicts kept themselves occupied by trying to get out of the penitentiary, one way or another.

By Any Means Possible

Almost immediately upon arrival, Dick Heath began working on a pardon.

He hadn’t forgotten what the police chief in Idaho Falls had said about being pardoned if he cooperated in the capture of Makley and Lanning. Heath decided to hold the chief to his word.

On the outside, his family helped by badgering the judge who had sentenced Heath. Grudgingly, the judge agreed that since this was Dick’s first arrest and he had cooperated, some leniency might be in store. It probably didn’t hurt that Heath’s grandfather had been a noteworthy figure in Blackfoot County.

Legal notices began to appear in the Idaho Register, notifying the public that William M. Heath was applying for a pardon. These notices started in May of 1910 and ran until the pardon board met in July.

In contrast to Heath’s progress, neither Lanning nor Makley had anyone trying to help them out, locally or otherwise. James Lanning listed a sister named Addie in Peoria, Illinois as next of kin while Charley Makley gave “Mr. and Mrs. Ed Makley” as his immediate family.

When contacted, Edward Makley did nothing and it appears, told no one of Charley’s whereabouts. As time passed, letters written to Charley by other members of his family to the Idaho Falls address were returned, unopened. Puzzled, they wondered what had happened to him.

Back at the penitentiary in the spring of 1910, most of the inmates, including Charley were caught up in the turmoil surrounding a double execution, scheduled for May 20th. At that time, condemned prisoners were hung. Executions were held on prison grounds in the yard, itself. A temporary gallows was constructed for each hanging and spectators from around the area often stood outside the penitentiary walls to view the event.

At the last minute, both men were granted stays of execution, one of the convicted, John Flemming, on grounds of insanity. Flemming was quoted in the local newspaper as saying “If they are going to do business with me, I wish they would get busy. I’m tired of the fiddling around.”

Things quieted down around the prison after the postponed executions. However, on July 6th, Dick was granted a full and unconditional pardon. A few days later, Warden Snook received a letter instructing him to release Heath immediately. Makley and Lanning were furious because they felt Heath had been rewarded for ratting them out.

After the pardon, “Dick” Heath seemed to have disappeared from the area. However in 1911, a “William” Heath (which was Dick’s formal name) was back in the news.

The Heath family was celebrating Thanksgiving at home. A turkey and all the trimmings along with a bottle of whiskey contributed to the festivities. Included in the family was a boarder by the name of John Taylor. By early Thanksgiving evening, Taylor had passed out on the floor. Young “William” wanted to continue the party and decided to go down town. When his mother wouldn’t give him a dollar, William tried to steal the dozing Taylor’s money but woke him up instead. A fight broke out. When the elder Heath tried to separate the two, his son struck him. The battle continued until neighbors hearing the ruckus, called the police.

All three were arrested. The following day, in municipal court, the senior Heath told the judge how his son had started the fight. Witnesses collaborated with his testimony. William Heath was convicted of disorderly conduct, disturbing the peace, and fighting. His father paid the fine and William Minard Heath left for good. A few years later, when the elder Minard Heath passed away, the wake would be held at the residence of James Lanning.

The Deadline

The summer of 1910 was one of the hottest on record. Northern Idaho and surrounding states were plagued with devastating forest fires caused by the heat and lack of rain. Even though the penitentiary sat in the southwest corner of the state, the inmates suffered from the blistering temperatures and perpetual haze caused by the fires.

While Charley stewed over Dick Heath’s lucky break, he and Lanning were recruited to help the other inmates thresh grain on the prison farm. Although the work was hot and dusty, Charley may have welcomed the opportunity to get outside the prison walls. And although he waited for a chance to simply walk away from the job, the guards were too vigilant.

Similar to the warden position, guard jobs were also political appointments. Training was fairly informal with the older guards explaining to the newer ones how to be “con-wise”.

Sometimes that wasn’t enough. There were more than five hundred escape attempts during the years the penitentiary was in operation. Out of that number, around ninety were successful. Most escapes were attempted when the prisoners were outside the penitentiary walls. But there were some who escaped from the inside.

As a deterrent to prevent escape attempts, a twelve to sixteen foot dirt perimeter called the Deadline was maintained between the prison walls and the yard itself. The Deadline was also known as “No Man’s Land” because inmates were not allowed to go into it without permission from the tower guards. If they disobeyed, they would be shot on site. Each and every day, the Deadline was raked so that suspicious footprints could be easily seen.

During the summer of 1910, because of the overcrowding, Makley and Lanning were being housed together in the top section of an older guard house which wasn’t very substantial. Work was almost completed on the new cell house which was regarded as being one of the most secure in the entire Northwest.

Shortly the boys would be moved into brand-new cells that had three foot thick stone floors, all steel bars and locks. In addition to a key, there was another locking device to access the cells, which was similar to the combination on a safe.

Upset because they felt that Dick Heath had set them up to take the fall, Charley Makley and James Lanning decided to escape. Although their best chance was trying to make a break outside prison walls, they hadn’t yet caught a lucky break. Both realized that once they were moved into the new cell house, their opportunities would be further reduced.

At the beginning of August, the boys spent their nights carefully removing stone and bricks from the wall of their cell in the guard house. They hoped to be able to squeeze out of the opening and slide down the side of the building between rounds of the guards. Once on the ground, the duo would make a mad dash for the Deadline and then try to scale the penitentiary wall.

Each morning, they would hide the debris from their nights work before their cell was inspected. Finally on a moonless night almost a month after Heath had left, they decided to make their break for freedom.

Unfortunately they had forgotten about one important thing, keeping tabs on the guards. Evidently the boys didn’t have a way to reliably time the guards as they went about their rounds. Lanning stuck his head out of the opening to ascertain where the guards were when he accidently made a noise. The guard looked up at the sound but mistook Lanning for an owl which frequented the penitentiary. Scared, Lanning retreated.

The guard became suspicious and reported the incident to the warden. By the next morning, the jig was up as the discovery of the hole in their cell told the story. Abashed both boys confessed.

Warden Snook may have felt a pang of pity for Makley and Lanning because he didn’t count their try as an official escape attempt. This may have saved the boys from being thrown into solitary confinement or as it was known as the “Bug House”.

Instead they became some of the first inmates to test out the brand-new cell house which officially opened several weeks later. However it’s doubtful that they stayed roommates. Although both were young, first-time offenders, Warden Snook didn’t want any more repeat performances.

A Carrot for Compliance

Although the depressing conditions and hard work made one day blend into the next, there were a few instances that brightened things for the prisoners. One was Thanksgiving.

On Thanksgiving morning of 1910, over two hundred men were entertained by “moving pictures” accompanied by an orchestra set up in the dining hall. Charley and his fellow prisoners partook of a feature length production and a two-part comedy. According to the local newspaper, a local song and dance team also appeared. The entertainment was a big hit for the convicts and guards alike. Later in the afternoon, a spread with turkey and the fixings was provided. The men were allowed to eat all that they could and take leftovers back to their cells.

Buoyed by the inmates’ reaction, Warden Snook decided to up the ante. For Christmas of 1911, here’s what took place:

To the extreme delight and unalloyed pleasure of themselves and some two hundred of their fellow prisoners, as well as a small audience of invited guests, the stars of “The Original Southern Minstrels” an organization of clever performers in the art of minstrelsy, made up of convicts at the state penitentiary, appeared in blackface in the dining hall at the institution yesterday afternoon and made merry in song, story and dance for two solid hours.

The performance was simply great- the music, the songs, the dances, the jokes, the improvised stage with its gaily painted curtains and modern electrical connections- all of these were good and more, but the finest feature of it all was the enthusiasm of the performers and the jolly appreciation of the other prisoners, who evidenced a keen enjoyment in each and every number and particularly in the jokes, of which the guards at the institution and some of the methods employed were made to bear the burden.

December 26, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise City Idaho

Even with the occasional entertainment, and the new cell house, the Idaho State Penitentiary continued to be a highly stressful place. However after their aborted escape attempt, both Makley and Lanning more or less tried to keep out of trouble. They had come to the realization that their sentences could be shortened by good behavior.

Early in 1912, the penitentiary housed two hundred and eighty-six men, the highest number it had ever held. The crowded conditions made it difficult for the prisoners and guards alike. Doubling up the convicts continued in cells that had been built to house just one man.

One way Warden Snook could ease the tight conditions was by paroling an inmate. This method was already being used as an incentive for good behavior. At the same time, prison reform was sweeping the country. Reformists were concerned with easing convicts back into society by providing them with skills that would allow them to compete equally with others. These changes relaxed the requirements so that more convicts were considered eligible for parole.

There was a gentleman in the Boise area, who assisted the inmates in finding jobs beyond the penitentiary. This “friend of parolees” not only helped place the men but worked diligently to keep their identities a secret so that they would have a better chance in the outside world.

However there were some who tried to take advantage of the paroled inmates. A local tax collector by the name of Clark ran afoul of Warden Snook when he shook down the men out on parole for two dollars apiece for a road poll tax. When Snook found out about the scam, he issued orders that no paroled prisoner should pay the tax. He reasoned that “the status of a paroled prisoner is exactly the same as that of a prisoner detained at the penitentiary, except that one happens to be out on trust while the other is held inside.”

Undeterred, Clark then demanded that Warden Snook provide him with a list of all the prisoners so that two dollars a head could be collected from the penitentiary. The State Attorney General had to step in to settle the matter in favor of the parolees.

The Silver Lining

The Idaho State Penitentiary parole board met several times each year on a fairly regular basis. In May of 1912, it convened to decide who had earned the privilege. There were forty applications, the most that had ever been presented to the board. Among the forty were Charley Makley and James Lanning. Of these forty requests, only sixteen were granted. One of those sixteen happened to be James Lanning. Charley was passed over.

It was a conditional parole. Under its terms, Lanning had to report to the sheriff of the county designated in his parole agreement. He could not leave the county without receiving prior permission from Warden Snook and could also not drink or gamble. Lanning was also to avoid “evil associates and improper places of amusement.”

On June 3rd, 1912, James Lanning was released in Ada County. He chose to remain in Boise, near the penitentiary. His incentive was May Heath who had moved there from Idaho Falls. By October of 1912, James Lanning and May Heath had gotten married.

Charley redoubled his efforts so that he could apply again in September. This time when the parole board met there were between thirty-five and forty applications. But this time he was met with success. On September 4th, 1912, Charley signed a parole agreement with Warden Snook, traded his prison uniform in for street clothes and headed out.

He would remain under Snook’s supervision until 1915, when his sentence was fulfilled. Although Charley also stayed in Ada County, he was discouraged from going to Boise. Instead he headed for a smaller place in the county that was experiencing a growth spurt during the fall of 1912.

During his years in Idaho, Charley Makley would do some growing as well, becoming a husband and father. But for now as he passed through the gates of the Idaho State Penitentiary, he had taken a few small steps towards reconciling with his past.

Back in the summer of 1910, a few months after his incarceration, Charley’s birth mother became frantic when one letter after the other bounced back from the Idaho Falls address unopened. Frustrated by the lack of information coming from St. Marys Ohio, she pled with one of Edward Makley’s brothers to intercede. Finally Ed relented, admitting what had happened. Relieved, his mother wrote to Warden Snook and to Charley. Only Snook replied. Ashamed because “I’d (sic) gotten some dirt on me”, Charley sent back his mother’s letter unopened and unanswered.

But a mother’s love is persistent. She continued to write, even sending another inquiry to Warden Snook asking whether Charley was still incarcerated or not. John Snook decided enough was enough. He convinced Makley to write back to his mother. Hesitantly he did.

For all his bluff and bluster, deep down Charley was an insecure person. He had been given up by his family as a young boy. Sent to live in a strange home, where he was considered less a son and more another mouth to feed, he may have been afraid that his mother was about to give up on him again.

Throughout his life, Charley would be surprised by who chose to stand by him (and those who didn’t) when the going got rough. This time was no exception. His mother would continue to care, keeping in touch with him until her death in 1923. And Charles Makley would return her love by naming his only daughter after her.

A Very Special Thanks to Rebecca Siple. Your investigative skills put J. Edgar and the rest of the boys at the Department of Justice to shame.

![]()

Sources:

Woman Slayer Nerveless on Trap, May 8, 1909, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Prison Packets for William Minard Heath, James Lanning, and Charley Makely, February 21, 1910, Old Idaho State Penitentiary, Boise, Idaho

Prison Order is Working Out Well, April 10, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Convicts Dash for Liberty Fails, April 21, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Thirteenth Census, May 3 1910, Precinct One, Boise, Idaho

Proposed Double Hanging is Postponed Indefinitely, May 12, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Legal Notices – Application for Pardon, W.M. Heath, June 3, 1910, Idaho Register, Idaho Falls, Idaho

Nerve Failed Them, August 9, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

New Cell House is Ready for Occupancy, August 22, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Raffles Caught with Aid of Bloodhound, October 29, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Swell Spreads Arranged for Thanksgiving, November, 16, 1910. Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Take Turkey to Cells, November 25, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Much Cash Needed for State Pen, December 20, 1910, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Road Poll Tax Taken From Prisoners, July 2, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Convicts Thresh Grain, September, 24, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Puddin’ Head Wilson System of Catching Criminals is Popular, November 10, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Son Starts Fight and Must Pay Penalty, December 2, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Christmas Minstrels to Lighten the Bloom at the Penitentiary, December 23, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Merry Christmas at Prison, December 26, 1911, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Ice Harvest Put Up for State Convicts, January 3, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Prison Reform Has Energetic Booster, January 15, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Warden Snook has Full House at Penitentiary, March 4, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Commissioners Parole 16 Convicts, June 19, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Convicts Seek Parole, September 4, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Parole Board Meets, September 5, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Friend of Convicts Keeps Identity a Secret, September 8, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

Cramer on Parole But Confined to Ada County, December 7, 1912, Idaho Statesman, Boise, Idaho

History of Idaho: a Narrative of Its Historical Progress, Its People and Its Principal Interests, Volume Two, Hiram Taylor French, MS, 1914, The Lewis Publishing Company, Chicago, Illinois, and New York, New York

A Place of Confinement: Constructing the Old Idaho State Penitentiary 1872 – 1973, Dr. Peter Wolheim, 1993

Photos:

- Charles Makley Mug Shot, Profile, February 1910, Old Idaho State Penitentiary, Idaho State Historical Society, Boise, Idaho

- Idaho State Penitentiary, Boise, Idaho (Gate), Undated, C. E. Harvey, Boise, Idaho, Authors Collection

- Warden’s Office Idaho State Penitentiary, 1912, Idaho Historical Society

- Ice Cutting, Undated, Montreal, Canada, Authors Collection

- Idaho State Penitentiary on The Old Oregon Trail, Undated, Wesley Andrews Co., Portland, Oregon, Authors Collection.

- Prisoners Outside Warden’s Office, Undated, Authors Collection

- Chain Gang, Undated, Authors Collection

- Dick Heath Mug Shot, Profile, February 1910, Old Idaho State Penitentiary, Idaho State Historical Society, Boise, Idaho

- Jail Break, Undated, Authors Collection

- Minstrel Show, Undated, Authors Collection

- Old Idaho State Penitentiary, 1987, Charles Hillinger, Los Angeles Times, Los Angeles, California

- James Lanning Mug Shot, Profile, February 1910, Old Idaho State Penitentiary, Idaho State Historical Society, Boise, Idaho

Copyright 2009 - 2016, all rights reserved